- Home

- What He Doesnt Know

Lisa Noeli Page 3

Lisa Noeli Read online

Page 3

Chapter Three

“Enter!” Lizzie trilled.

Josephine opened the door and looked around it to see the singer standing in front of a tall mirror. Lizzie was clutching an unfastened corset to her magnificent bosom. Other than that, she wore only drawers and seemed not to care who saw what.

Jo looked away. A blithe disregard for propriety was simply a part of life in the theater, but Jo was not yet used to such brazenness.

“Hallo, Josie,” the singer said cheerfully. “You are about to witness a miracle.”

Dora, Lizzie’s dresser, wrapped the corset laces around her hands and seemed to say a silent prayer. Then she pulled with all her might, stopping only to wipe the sweat from her brow.

“Oof!” Lizzie exclaimed. “Can’t breathe, let alone sing!”

Dora loosened the laces just a little.

“Thank you.” Lizzie let out a few experimental tra-la-las and a lace snapped. “No, this one won’t do. Four strong men could not fasten my stays.” She slapped her thick middle and gave her reflection a satisfied smile. “I like to eat.”

Her dresser scowled and unwound the broken lace from one hand, letting the other dangle from the back of the corset.

“Don’t look so cross, Dora. I don’t care. Find a bigger corset or two in the wardrobe room and bring them back quick, before I get any plumper. And bring back four strong men while you’re at it. Much obliged!” Lizzie let out a bawdy laugh.

Dora managed a small smile. “Yes, Miss Loudermilk.”

Waiting to one side was the wardrobe mistress, Ginny Goodchurch, who also served in an unofficial capacity as mother hen of the company. Her arms were full of costumes and a pincushion was strapped to one wrist. A wicked-looking pair of shears hung from a cord around her neck.

“Jo, dear,” Ginny said, “we was in the middle of a fitting, as ye can see. Can ye help?”

“Of course.”

“Get one that is two sizes larger. Or three,” Lizzie instructed Dora, wriggling out of the corset and handing it to her. “Dear Lord, I am ever so tired of squeezing myself into things. This show shall be the end of my brilliant career. I can’t wait.”

“Do not say that, Miss Loudermilk,” Dora said, looking shocked. “The public will never let ye retire.”

“Damn the public. I have grown weary of caterwauling for a living. And I have saved enough to retire in solitary splendor.”

“But what about the old general? He has been yer devoted admirer for all these years. He will want to marry ye.”

Lizzie sniffed. “I doubt it. And I do not want to marry him.”

“Think of all the roses and diamonds he has given ye,” Dora murmured. “And didn’t he write the poem about the heavenly stars that twinkle in yer eyes?”

“No. You must be thinking of the old admiral. He was always writing poetry when he should have been off fighting the filthy French. Military men are not what they used to be, though I will always love a uniform.”

“Still, it were a lovely poem,” Dora said stubbornly. “You kept it in yer album for the longest time.”

“Did I?” Lizzie shrugged. “It meant nothing to me.”

The dresser heaved a sigh and left the room with the corset.

“She is an incurable romantic. But I am not.” Lizzie studied herself in the mirror, pulling up the loose skin under her chin and frowning. “I am getting old myself. But I have no wish to listen to the general grumble about his gouty toe and the ill wind that blows through his guts. I would rather amuse myself alone or enjoy the company of dear friends—and I have many.”

Ginny laughed. “And I count meself among them. But I am not sure young Jo should hear such cynical talk.”

“It is the truth, Ginny. Besides, Jo has a beautiful voice that may well prove to be her fortune. What woman would marry if she could earn a handsome living on her own?” Lizzie favored Jo with a shrewd smile and returned to the contemplation of her reflection.

Josephine gaped at Lizzie’s back, startled beyond words by the unexpected compliment. As to the rest of it, Lizzie had a point.

But … there was no escaping the social rules and conventions that shaped women’s lives, however much Jo might relish her freedom at the moment and however tempting independence might seem. She would never go on the stage. No decent woman did.

“What d’ye think, Jo?” the wardrobe mistress asked. “D’ye hope to marry? I expect ye have a sweetheart.”

“Ah, I do not. As for marrying, I could not say. But it is certainly very kind of Miss Loudermilk to praise my singing.”

Lizzie guffawed. “Don’t be mealy-mouthed, my girl. If you want all of London at your feet, you have what it takes. I know a fine voice when I hear one. But do not step into my spotlight. Not yet.”

Ginny held out the costumes. “I’m sure our Jo has more sense than that. Now choose, Lizzie dear. I haven’t got all day.”

“Is it day? Or night? I can never tell when I’m working, and there are no windows in these stuffy little dressing rooms. We never get a breath of fresh air. Never see the sky. Never hear a sparrow sing. Strike up the violins, someone.”

“Ye’re a proper sketch, Lizzie,” the wardrobe mistress said fondly.

Lizzie grinned and poked through the brightly colored heap of dresses in Ginny’s arms. She selected a striped gown. “This one. The stripes will make me look a stone or two lighter.”

“I thought ye didn’t care,” Ginny teased.

“Shut up or I’ll have you sacked. The color is flattering. Can you let out the seams?”

Ginny set the others down and held the striped gown up to Lizzie’s big body. “There might be enough material, ye great cow.” She glanced over as the door opened and the dresser entered. “Here is Dora. Jo and I will pick out the seams while ye try on more corsets. Good luck.”

Josephine and Ginny turned the gown inside out and spread it between them on the sofa. They concentrated on the painstaking task of unpicking the seams, and soon had the back and front of the gown apart.

Ginny examined the pieces carefully. “More than enough—there is at least an extra two inches.”

“Good,” Lizzie said, winking at the wardrobe mistress. “Make the most of it.”

Ginny turned to Jo. “Watch how I do it so ye can learn. But it will be faster if I do the sewing meself.”

Josephine knew that the wardrobe mistress was being tactful. She had tried once before to help Ginny sew, but as with her embroidery at home, the thread tangled and the needle slipped from her fingers, until she gave up in disgust.

Ginny looked for matching thread, but there was none in her basket. She set aside the pieces of the gown and walked to the door.

“Where are you off to?” Lizzie asked, tucking her overflowing bosom into the corset Dora had just put around her. Her breasts popped back up. “Blast. We need the biggest one, I’m afraid.”

“Well, I need thread.”

Lizzie nodded regally. “You may go.”

Ginny rolled her eyes for Jo’s benefit and left the room. Lizzie and Dora wrestled with another set of stays, talking in low voices, while Jo leaned back on the squeaky old sofa and looked around the dressing room.

Like all theater folk, Lizzie Loudermilk was superstitious—and messy. The dressing table, folding screen, and walls were decorated with trinkets that were supposed to bring luck. Imitation pearl necklaces and sham jewels dangled from the candle-holders on either side of the dressing table mirror. Letters from admirers and invitations to dances and dinners were tucked into its frame.

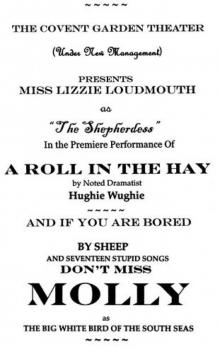

A faded garter had pride of place at the mirror’s top. Ginny had explained that Lizzie had worn it for her triumphant debut at Covent Garden years ago, when Ginny and the singer had met for the first time.

Josephine tried to imagine singing while looking out on a crowd of more than three thousand people. She could never do it—not with her eyes open, anyway.

She rose and went to the dressing table, casting a glance into the hinged

, multicompartmented case that sat upon it. Each compartment held something different: small brushes, sticks of charcoal, powdered pigments wrapped in crinkly paper, tiny velvet patches, strange bits of rubber, and little pots of thick paint.

Josephine picked up a brush and touched it to her palm, surprised by the softness of the bristles.

Lizzie smiled. “That’s sable, love. Made especially for me. Dip it in the pink powder and give yourself nice rosy cheeks. You look a bit pale.”

Josephine hastily set down the brush. “I would never.”

“What are you afraid of?”

My mother, Jo wanted to say. My father. Everyone in Richmond. She reminded herself that she was in London. If she wanted to look like a rosy-cheeked milkmaid—or an Indian queen or a wicked witch—they would never know. She picked up the brush again.

“Go ahead, you little goose. Have a bit of fun.”

Dora gave Josephine an encouraging smile. “Yes, do. It is only paint and powder, miss.” She pointed to a fat jar in front of the mirror. “That there is a cream to take it all off again.”

Jo sat down in front of the mirror and stared at her reflection. She saw what she always saw: regular features, pale skin with a few freckles, a curving mouth with a full lower lip. Her eyes were a mix of blue and green, with long lashes. Her hair was the color of honey and she wore it up, with a fringe.

She looked no different than yesterday but she suddenly felt different. Bolder. Naughtier. Ready for a change.

“Very well, I will.”

She opened a packet of pink powder and dipped the brush into it, then dabbed the powder on her cheeks. But the color was too bright against her skin and the circles were too even.

“I look like a clown,” she said with dismay.

“Try again. Takes practice,” Lizzie said.

Josephine picked up a rag and tried to wipe away the powder, to no avail.

“Ye have to use the cream,” Dora reminded her. “But ye can put on a color over the powder if you like. Try this one.” She selected a pot of skin-colored paint and opened it, setting it down in front of Jo, who wrinkled her nose.

“It smells bad.”

“You get used to it,” Lizzie said philosophically.

Josephine gave her a doubtful look. She wasn’t at all sure that she wanted to. “But how do I put it on?”

“With yer fingertips. ’Tis greasy, miss. So ye can’t use the sable brush. And ye won’t want to get it in yer hair. Here, let me.” Dora picked up a piece of fine gauze and wound it tightly around Jo’s head, tucking every last strand of hair underneath.

Jo peered in the mirror again. “Oh, dear. Now I look like a bald clown.”

Dora laughed. “D’ye want me to show ye how to put on a face?”

“Yes, please do. I shall never manage on my own.”

With Lizzie on one side making suggestions and Dora on the other doing the work, Jo watched in the mirror as an amazing transformation took place. Her plain self gradually disappeared … and a bewitching creature with arched eyebrows, ruby lips, and a china-doll complexion took her place. When Dora removed the gauze to redo Josephine’s hair, she scarcely recognized herself.

Dora pinned up Jo’s hair anew, and Lizzie added a collar of imitation pearls and paste earbobs. In the candlelight, they looked real enough, and Josephine looked spectacular.

“You are a beauty, miss,” Dora said admiringly.

Lizzie nodded. “I must agree.”

“It is only the paint,” Jo said hastily. “That’s not me.”

“It is you,” Lizzie replied. “Do you know, looking at you makes me feel tired. Very tired. And very old.”

“You are not old, Miss Loudermilk,” Dora said quietly.

“At the moment, I feel older than Mrs. Methuselah. Unless Methuselah was married to a younger woman—I’m sure he was. All the old goats want a young woman. That is a fact of life, Josephine. Make a note of it.”

Jo didn’t know whether to laugh or say something sympathetic. She had intended only to amuse herself, not to show up Lizzie.

But Jo had not expected to look so … dazzling. She had never looked dazzling before. It was an interesting sensation. She peered into the mirror again to see whether the beautiful lady had gone away. No, there she was.

“Look your fill,” Lizzie said gloomily. “Enjoy it while it lasts and gather ye rosebuds while ye may, et cetera. Perhaps I should have a lie-down.” She got up with a dejected sigh and went over to the sofa, pulling a tattered old blanket up over her face. “It is later than I think.”

Jo looked worriedly at Dora and then back in the mirror. She knew that it was a face for the footlights and not in the least real, but her transformation had certainly alarmed Lizzie. Jo wondered whether to reassure the singer.

“Never mind her, miss. She’ll stop sulking soon enough,” Dora said rather loudly.

“I am not sulking,” the old blanket replied with muffled dignity. “I am resting. And planning my retirement from the stage. I mean it this time. This show will definitely mark my final appearance upon the boards.”

“Ye keep sayin’ that, Miss Loudermilk. And I keep tellin’ ye, the public will not let ye retire.”

A knock on the door made Lizzie fling off the blanket and sit up. Her riotous red hair curled in every direction and spilled over her shoulders. The two women at the dressing table turned around.

“Now who do ye suppose that is?” Dora asked.

“Ask,” Lizzie hissed. “Ginny would not knock.”

There was another knock. “Hello? Is Miss Loudermilk within?”

“Yes, kind sir, I sit and spin,” she sang under her breath.

“One of your greatest admirers would like to meet you.”

Jo recognized her brother’s voice. “It is Terence … and he would not like to see me painted and powdered.”

“Then get in the closet,” Lizzie said, rolling her eyes. “Always a good beginning for a farce.”

Josephine took a deep breath. At least Lord York had left the theater. She would be dreadfully embarrassed if he saw her like this. Even if her brother was accompanied by a stranger, she would still be embarrassed. She decided that she might as well hide.

“One moment,” Lizzie called. She got up and threw on a threadbare robe of greenish-gray material, inspecting herself in the tall mirror. “Dear God, it is later than I think. I look dead.” She whipped off the robe, found another in a flattering peach color and put it on instead. “Are you with the admiral or the general?” she called to the door.

“Neither,” Terence said from the other side.

“What do I care?” Lizzie muttered. “I need an admirer at the moment. Any bloke will do.” She cast a look at Josephine. “Quick! Into the closet!”

Chapter Four

From inside the closet, Jo heard her brother enter. She clutched the doors from the inside—they had not latched.

“Only two of you?” he said, nodding to Dora. “I thought I heard three voices.”

Lizzie made a great fuss over tying the sash of her robe and tossed her hair. “No, just us.” She cast an appraising glance at Lord York.

“Miss Loudermilk, allow me to introduce Lord York.”

“How do you do.”

Drat and double drat, Jo thought. Lord York had not gone after all.

Her nose twitched. She could not sneeze. The thick, greasy makeup began to itch. She could not let go of the doors to scratch. She fervently hoped and prayed that their visitors would pay Lizzie the extravagant compliments that the singer craved, and leave at once.

She heard someone settle onto the squeaky old sofa, and then a faint thump. This she recognized as the sound of good leather boots crossing at the ankle. Damnation. Did Terence have nothing better to do than loiter in dressing rooms?

“Hello, Ginny,” he said.

“Hello, Mr. Shy.” The wardrobe mistress came in and spoke to Lizzie. “I cannot find the exact color. I will have to go out and buy more thread. O

r I might send Jo. Where is she?”

Josephine winced.

“Yes, where is my sister?” Terence asked. “We thought we might find her here. The dancers told me they saw her head off this way.”

“Did they?” said Lizzie. “Oh, um, she was here but she went out to … to the apothecary. For medicated gargle. For my throat. She is a dear and always so thoughtful.”

“Ah, yes,” Lord York said. “She is a dear. How does Jo like London, Terence? And does she still sing? I remember her warbling in the lanes of Richmond.”

You do? Jo opened her mouth in surprise, then shut it quickly.

“She had a lovely voice, even when she was very young,” Lord York went on. “Do you recollect that musical evening at Derrydale, when she and I sang a duet?”

“Vaguely,” Terence said.

“You and I were seventeen.”

“And she was a brat of eight.” Terence laughed.

“Then you and I remember her differently. She was charming, even as a child. I seldom saw her after that, and then only at a distance, but she did seem to have grown into a lovely young woman.”

Thank you very much, Jo thought crossly, rubbing her itchy nose against the door. You might have told me. No doubt Lord York thought himself too grand for a mere vicar’s daughter.

“Has she married?” he asked.

“No.”

Why did he want to know?

“You never did say if she likes London, Terence.”

“She seems to like it well enough. She is a busy little bee and quite domestic—she keeps house for me, you know.”

Liar.

“And she never comes to the theater,” Terence said firmly. “Well, almost never.”

“I should think she would be tempted to sing upon that marvelous stage, if only to an empty house.”

“Jo? Not at all. No decent woman would even think of such a thing.”

“But if no one was listening and no one knew, Terence, what would it matter?”

The two men pondered that conundrum for a moment.

Lizzie, who hated to be ignored, stamped a foot. “Am I not a decent woman? And what is wrong with singing in a theater? There are worse ways to make money. At least theater folk are honest—and virtuous when it counts.”

Lisa Noeli

Lisa Noeli